In today’s fast-paced society, where days and weeks seem to rush by more quickly than ever, it seems the only time we stop to appreciate our amazingly constructed figures is at 6 a.m. when we look in the mirror to brush our teeth or apply makeup. Most people aren’t even in touch with what their bodies look like (especially the backside). Our bodies, which come in all shapes and sizes, are complex and wonderfully crafted works of art that deserve more attention.

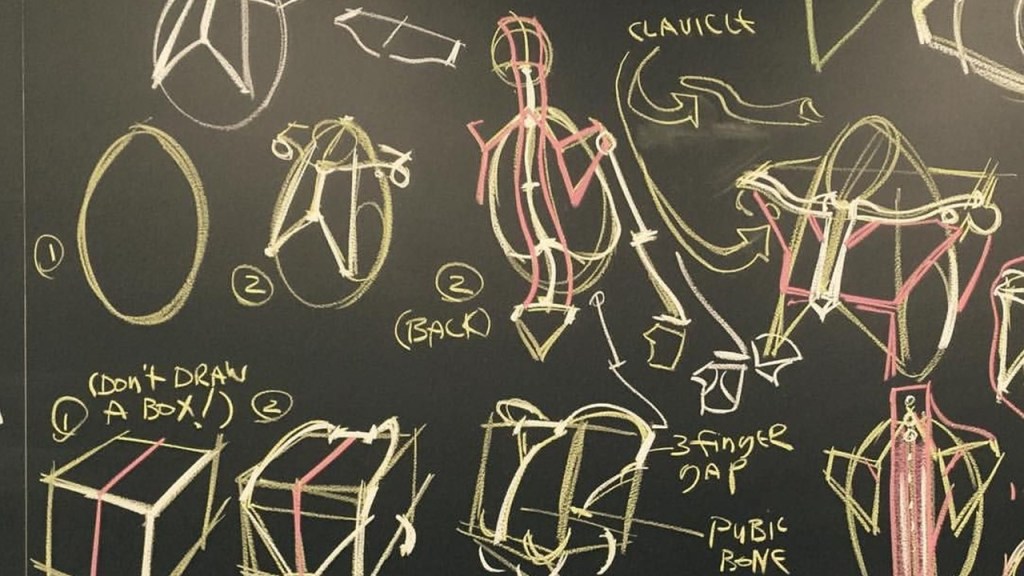

Figure-drawing students approach me on the first day of class, claiming they can draw only stick figures, but most gain two things by the end of the first session. One: they realize how beautiful yet complex the body is. Two: they realize how talented they are and how fun it is to apply their skills to drawing the human figure. Whether you’re an art student, a professional illustrator wanting to brush up on your figure-drawing skills, or just someone who likes to doodle and wants some guidance on drawing the figure, learning figure drawing is a great place to start.